by J.A. Myhre

The majority of the world’s children wake up each day to a life of relative danger: tenuous food supplies, the lurking threat of violence, unregulated pollution, microbe-laden water, distant or inaccessible health care, substandard schools. And a significant portion of those face much worse: recruitment as child soldiers, exploitation by traffickers, physical disabilities, or the lonely vulnerability of being orphaned. Nearly six million children under age 5 won’t live through 2016, due primarily to poverty-related causes: lack of medical care and needed vaccinations, or living in an areas where malaria is endemic.

The world, in short, is a dangerous place for many children.

Parents the world over seek to protect their children, as much as possible. We value security for those we love. Though we may be thrown off-balance by threats of terrorism or cancer or unintentional injuries, parents in privileged countries can largely expect that their children will have enough to eat, a school to attend, and protection from many of the dangers of war and disease.

Many parents in North America are left with the dilemma: How do I raise a confident, secure child in a world of uncertainty? How much should my child know about the evils of this world? Wouldn’t it be better to shield them completely?

First, let us put to rest the possibility that complete shielding is possible. Even if you were to raise your children in isolation from the internet, television, literature, neighbors or classmates, or any influence other than your own, we know that they would still encounter evil. Why? Because, as the famous line from Solzhenitsyn reminds us, the line between good and evil runs through every human heart. Our hearts and our children’s would still confront the ugliness of jealousy, lies, greed, fear, manipulation, harshness, and other sins with no input necessary from evils outside the home. And eventually those children would have to cross the threshold where the spectrum of evil broadens. So the real question we are asking becomes, how can we prepare our children for the realities of evil in a way that maximizes resilience and minimizes scars?The key tool, I believe, has been given to all of us by our Heavenly Father: Story.God’s chosen method of communicating truth to us over the ages has been the spoken and written word. And He tells us to do the same for our kids.

In Psalm 78, the Psalmist Asaph says:“I will open my mouth in a parable; I will utter dark saying of old, Which we have heard and known,And our fathers have told us. We will not hide them from their children, Telling to the generation to come the praises of the LORD, And his strength and His wonderful works that He has done. He commanded our fathers,That they should make them known to their children, That the generation to come might know them, The children who would be bornThat they may set their hope in God.”

Then the Psalm goes on to list a lot of darkness and sorrow. Rebellion, confusion, wind, dust, anger, provocation, wilderness, sword and fire. Hardly the stuff of children’s stories. Yet we learn from the Bible several important answers to this parental dilemma, and several principles for the use of story.

First, evil is the context for the praises of the LORD. The more we see of the brokenness and desperation of this fallen world, the more we know the greatness of God’s rescue. In the foundational giving of the Law in Deuteronomy, parents were specifically enjoined to teach their children about the slavery they suffered in Egypt, the horrific judgment plagues, the marvelous deliverance as the seas parted. The evil of our own hearts, known to God and forgiven by grace, similarly drives us to marvel at God’s mercy and love. If we paint a world of tepid, moderate problems, we then minimize the astounding contrast of redemption.

Second, including evil in the story validates what a child already instinctively senses. We do not do our children a favor if we pretend that all is well. By giving the honest account of wilderness, wanderings, captivity and exile, children learn that their natural propensity to abhor evil and long for good have a basis in the story of the world. Evil is not presented as titillating or fun, nor is it watered down or excused. Evil is called out for just what it is: frightening and wrong.Note, though, that evil is the backdrop and not the climax of the story. The Bible is certainly not rated G. Babies are slaughtered and thrown into fires. A teenage girl trains to join a harem. A priest’s concubine dies from a night of abuse and is then cut in pieces and mailed to the tribes to instigate war. Bone-chilling evil which is not glossed over forms a thread through much of the narrative. But the story does not glorify this evil. It is part of the story, but not the point of the story.

Last of all, in the story of Scripture, evil has a limit and an end. The sweep of the narrative builds from a perfect creation ruined as paradise is lost, to an undercover King come to regain His lands, who walks with agonizing, willful determination right into the hands of evil and death. Just as darkness seems to have won the day, the King conquers death for all time and is resurrected as the beginning of a New Heavens and New Earth. But rather than aggressively stamping out all evil at that moment, He gives His followers the mission to go out to the ends of the earth with the good news so that people everywhere can choose life. In the mystery of the universe, God works in hidden ways, winning humanity back from the clutches of evil and carefully preserving good. And the story closes with a vision of the ultimate end of all evil, the eternal reign of a city of light where tears are no more.

So from Scripture we can conclude that evil forms an important part of the story of God’s power and love we are to tell our children, but we also see that within that story evil is temporary and limited. What is the impact on a child, then, of interacting with evil in a story?

Provided the story is appropriate to the child’s developmental age, acknowledging the fear-inducing and sad aspects of life can be healthy. Following characters, to whom kids can relate and testing the outcomes of choices can be an empowering way for children to get a grip on a world that might otherwise seem completely chaotic or unfair. A child is reassured that he or she is not the only one facing the loss of a parent or the humiliation of bullying, or worse.

Presenting evil in the form of a story not only helps young people process their own experiences, but allows them to build empathy for others whose experiences may be different. In 2016, our North American kids may not experience the threat of becoming refugees, but don’t we want them to understand something of the experience of thousands and thousands of other children? Won’t this equip them, one day, to make decisions based on wisdom and justice for all?

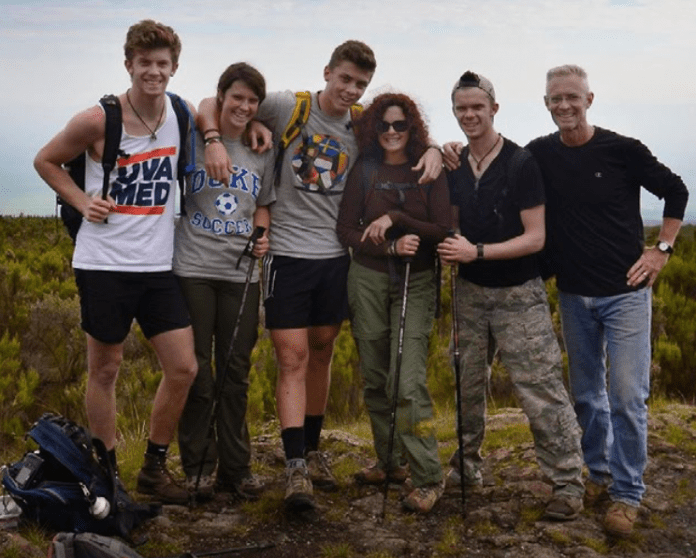

As a parent and a pediatrician raising four children, I wanted my own kids to struggle with the broken evils of this world in stories that put their experiences into perspective and offered hope. I had no illusions that mine would be oblivious of evil. They grew up on the Uganda-Congo border, in a remote valley marked by both beauty and poverty. They and their friends knew how to take cover from gunfire. They saw sick babies brought to us for treatment. They attended funerals. They had to overcome the stigma of being outsiders. Structural evil, interpersonal evil and biological evil all clouded their childhoods. But stories that had strong African settings and characters for their age group were difficult to find. So one year, I wrote them a short novel for Christmas, in a genre I would call “young adult magical realism.” I gave them a character who faced some of the worst evils that could befall a young child: being an orphan, being trafficked, being injured, being lost, being desperate enough to betray a friend. But those tragedies come within the fabric of a story that also includes purpose, hope, and ultimately, redemption.

The result is a book called A Chameleon, A Boy, and A Quest, and that started an annual Christmas tradition for the next four years. This year the second book of the series, A Girl, A Bird, and A Rescue, will be published as well. I believe that stories like these attempt to strike the right balance of acknowledging evil, but pointing to the deeper truth that all shall be well in the end. Our kids need that–from their stories…and from us.

Purchase your copy of J.A. Myhre’s book

“A Chameleon, a Boy, and a Quest”

today at:

http://stores.newgrowthpress.com/a-chameleon-a-boy-and-a-quest/

Jennifer Myhre, MD, serves as a doctor with Serge in East Africa where she has worked for over two decades. She is passionate about health care for the poor, training local doctors and nurses, promoting childhood nutrition and development, and being the hands of Jesus in the hardest places.